-

-

DIY Flower Arrangements,

you don’t need a florist if you have a garden.

-

Painting the Landscape with Fire

The history of land management co-evolved with the ecology of fire. Tens of thousands of years ago, Native Americans burned tracts of land. Amongst the reasons were clearance for sight lines, setting up villages, protection from enemies, and the cultivation of land through agriculture. These fires, especially in the southeastern United States, regenerated the land and reset them from stages of succession. Plants, trees, eco-systems, habitats, and plant communities developed adaptations to survive, regenerate, and thrive after burning.

Prior to human involvement, lightning strikes made fire obligatory in the landscape at regular intervals and shaped the land into grasslands and savannahs. European settlers followed and they rapidly learned the benefits of fire to aid their dependance on hunting and herding in the open landscapes.

Whatever the history and reasons, prescribed fire became an essential management tool in fire adapted ecosystems to restore equilibrium, increase health and control vegetation. Fire keeps the land more open thereby allowing sunlight to reach the herbaceous ground cover layer. Otherwise, without management, the thick understory shrub layer would outcompete the herbaceous layer through succession.

Fire is also economical and efficient. The other alternatives of mechanical removal and chemical herbicide control of undesired and aggressive vines and shrubs have cost and ecological downsides. Depending on the area of the country you are in, plants such as Chinaberry, Chinese Tallow Tree, Japanese Honeysuckle, Chinese Privet, and miscellaneous aggressive vines can be controlled efficiently through fire.

Prescribed fire is an art and a science. It depends on many simultaneous factors for a successful burn. As with everything, nothing beats the repetition of experience. For a successful and responsible burn, many simulaneous factors are essential: synching up a favorable weather forecast, specific weather conditions, acceptable humidity levels, changing wind patterns, and rainfall. Strategies such as fire breaks and discing the land aid in controlling and limiting the spread of fire. Backfires are often used to burn against the flow of the wind patterns to slow the spread and temperatures of the fire. Headfires are lighting with the wind which is used sparingly because it can move the fire rapidly and more out of control. Spotfires and flanking fires are other additional techniques in the arsenal of the fire manager.

Knowledge of what you are burning and how much you are burning is required prior to lighting a drip torch. The plant debris or fuel determines what the fire will do and where it will go. Mathematical estimations of fuel loads as well as science such as ventilation rates, dispersion, inversion, and air stagnation play essential roles in how the fire interacts with the landscape. Burn maps and plans are often drafted well in advance of burning. Periodic fire keeps fuel loads lower and limits the spread of larger, more uncontrolled fire. Smoke is as much of a threat as fire to nearby roads, highways and communities.

In conclusion, prescribed fire is an essential management tool for the landscape. Specific plants communities, like Maritime Forests and Longleaf Pine savannahs depend on it for survival. In an age of increased fragmentation and development, fire needs to be understood and practiced with responsibility and purpose. The present day and future of prescribed burns will continue to evolve as climate changes patterns, human development increases and fragmentation scars the landscape.

-

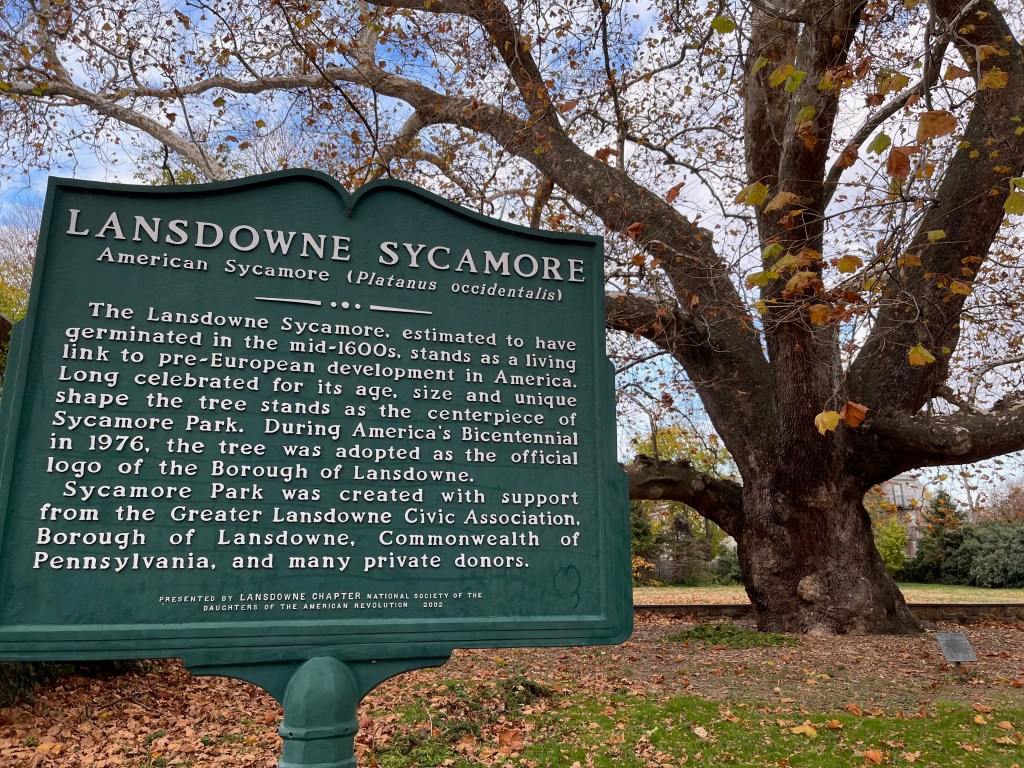

Sycamore Park, Pennsylvania

Everyone has a favorite garden, park, or natural lands getaway. This is mine.

Sycamore Park in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania on the borderline to Philadelphia is a small community park showcasing one very large, very old Sycamore tree, surrounded by turfgrass and within a perimeter of brick row houses. I grew up near this 300-350 year old American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis). While many parks, gardens, non-profits, and private landscapes struggle with goals, purpose, constraints of maintenance, and reason to be – this park does not.

The park is interwoven into the fabric of the Lansdowne / Upper Darby / Drexel Hill community. The location on a quiet residential street keeps it hidden and isolated from many visitors. Socially, events like birthday parties are held there. There is something ancient and human about a tree symbolized and used as the centerpiece of a park and community. I imagine the Romans and Gauls did the same thing. Native Americans did too, sometimes with nefarious outcomes. For example, the story of the Lenape Indians, William Penn, and the Treaty of Shackamaxon under the majestic Elm at what is now Penn Treaty Park.

Maintenance at Sycamore Park is fairly low. Occasional lawn crews mow the grass where neighborhood kids gather to play football. Old people and locals sit on the wooden bench to watch the surroundings. From a landscape design perspective, Sycamore Park is a statement in subtlety balancing functionality, community engagement, and sense of place. My criteria for a successful landscape is a balance of these elements with also an emphasis on the aesthetic, the functional, and the ecological.

In autumn, Sycamore leaves fall and cover the base of the tree. Local maintenance crews leave the leaves in place as a functional and convenient mulch adding productive biological and fungal properties to the soil.

Attributes of the stately Sycamore include the wonderfully smooth white bark, the oversized maple type leaf, and the hanging spiked seed balls. Old Native American lore says that Native Americans would plant Sycamores along riverbanks and wet areas, marking their locations.

-

Coastal Trillium

Trillium! Marvel of the woodlands. Jeffersonia, Trout Lily, Thalictrum, the mighty Bloodroot. These are the spring ephemerals. These are my plants during days when nothing else really happens. Their emergence signals that the cyclical circle of seasons has not been disrupted. Everything is in order and all has been restored.

Trillium. Three leaves, three sepals, three petals. Trillium are woodland plants that awaken under the sun of deciduous trees as spring ephemerals.

There is a distinction between the majority of northeast and southeast trillium. The majority of northeast Trillium are pedunculate which means the flowers hang on a stem. The leaves of these Trillium are predominantly green. In the southeast, the Trillium are called sessile with the flower sitting directly on the leaves. Sessile Trillium showcase distinctly kaleidoscope camouflage leaves.

There is much Trillium diversity in the south with over 30 different species. However, many are in the mountains. In the coastal plain, there is 1 species called Trillium maculatum or a slew of common names including spotted toadshade, mottled toad shade, spotted wake robin, spotted trillium, depending on your vernacular. The flower resembles a flickering flashing flame while flaunting flashy inkblot leaf patterns. These sessile Trillium multiply in clumps and also by seed.

Young Trillium Trillium maculatum grows in calcareous (high pH and nutrient rich) bluffs in mesic woodlands between Charleston and the middle of Florida. The soil in these coastal mesic woodland areas is unique. Years and years of Native American oyster shells collecting, gathering, and dumping in these areas loaded the soil with calcium carbonate which raises the pH and makes more nutrients available to the plants. Other unique to the southeast plants that grow in these plant communities include Red Buckeye, Indian Pink, Tulip Poplars, Bloodroot, and Black Walnut.

Trillium growing with Bloodroot These Trillium grow naturally on a sea island in Beaufort County, South Carolina. They grow approximately 1000 feet away from this salt water tidal river scene.

Other miscellaneous information about Trillium is that they are monocots and used to be classified in the lily family. They are pollinated by fungus gnats. The fragrances of flower between species vary between rotting meat and lemon-y dish soap. Trillium maculatum has the privilege of the latter. They produce sugary seed fruit clumps called elaiosomes which wasps, ants, and bees haul away to eat while depositing seed in the soil. Last but not least, as a retired Michigan school teacher, Fred Case and his wife Roberta were the king and queen of Trillium and wrote a wonderfully recommended book titled Trillium.

-

the Ballad of the Saguaro

Driving east from Phoenix, it began to rain and started to smell of Creosote.

Fully aware that many things do not live up to preconceived ideas and expectations, sometimes things do. For years, I have wanted to see Saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) but never had the opportunity to experience the plant in its habitat of sky, creatures, sounds, birds, and colors. Over the years and after different travel stops in East Texas, West Texas, and assorted botanical gardens, I had examined several transplanted versions of Saguaros in cultivation but not in the wild. These examples showcase attributes of the plant but lack the full picture cohesion of experiencing the plant in its native habitat. Like seeing an animal in a cage at the zoo. I embarked on a work-related trip into the Superstition Mountains of Arizona, within the heart (or at least artery) of the Saguaro cactus range.

There are four distinct deserts in the United States; the Great Basin, the Mojave, Sonoran and Chihuahuan. A desert is generally defined as an ecosystem with limited annual rainfall. Arizona uniquely has examples all four deserts. The Saguaro cactus only grows in the Sonoran desert.

Along Route 60 heading east from Phoenix to the mining town of Globe, skyscrapers of Saguaros dot the landscape like buildings of a city. From long gone Native American history and into the present day, the quiet stillness of the Saguaro radiates through the desert landscape. Like many things of significance, this cactus grows slow. Their lifespans contain multitudes, multiplying that of a human. The cactus reaches maturity around 125 years of age, flower after 35 years, and branches their arms between 50 and 100 years old. Some plants live over 200 years. According to the National Park Service, studies indicate that a saguaro grows between 1 and 1.5 inches in the first eight years of its life, often growing under the caretaker guidance of nurse trees where seedlings can glean nutrients and water while staying shaded.

With their columnar frames resembling statues across the landscape, Saguaros can grow 50 feet tall.

The tree-like Saguaro cactus are marvels of adaptation. Their form mirrors their function which is primarily water storage. Saguaros can weigh 6 tons or more. This tremendous weight is supported by a circular skeleton of interconnected, woody ribs. The number of ribs inside the plant correspond to the number of pleats on the outside of the plant. The roots grow from the plant radially, several inches beneath the ground. During a heavy rain, a saguaro will absorb as much water as its root system allows. To accommodate this potentially large influx of water, the pleats expand like an accordion. Conversely, when the desert is dry, the saguaro uses its stored water and the pleats contract.

Sagauros can be found growing within a complex plant community of Palo verde, Ironwood, Agaves, Yucca, Mesquite, & dazzling Dasylirions. Counter to the traditional idea of barren deserts, these habitats are brimming with life. Low, flat scrub desert can be sizzling hot and unsuitable for plants and creatures. But, high desert is different. The higher the elevation, the more variation in temperature and the more diverse the habitat. The higher the elevation, the colder the lowest temperature can get. Microclimates are then formed through directional exposure.

Saguaro cacti are host to a great variety of animals. In late summer, purplish red fruit called bahidaj ripens and provides food nourishment for animals during a time of scarcity. Other animals like jack rabbits, bighorn sheep, and mule deer eat saguaro flesh during times of desperation for hydration. An array of creatures such as the gilded flicker, elf owls, screech owls, purple martins, finches hawks, ravens, great horned owls, and the Gila woodpecker all utilize the cacti for nesting, protection, and platforms for hunting.

Through time, indigenous people resourcefully used the Saguaro cactus, as well. The fruit was gathered to make ceremonial jelly, candy, and wine. The strong, woody ribs were gathered to construct the framework for the walls of homes.

Like everything, there are limitations and threats to the prosperity of the Saguaro. Freezing temperatures also play a role in corralling the cactus. Elevation, and directional exposure limits the range of the plant as they are generally found growing from sea level to approximately 4,000 feet in elevation. Saguaros growing higher than 4,000 feet are usually found on south facing slopes where freezing temperatures are less likely to occur or are shorter in duration.

The biggest threat to the Saguaro is expanding human population and development of new homes. Exotic grasses like Buffelgrass were introduced in the 1970s as problemsolvers for erosion control and cattle feed. Soon after, Buffelgrass began turning the desert into a grassland, invading undisturbed areas of the desert and roadside. Then, due to the fire adaptability of the grass, fire spread much more easily. Saguaros are not fire adapted and the large scale escalation of brushfires are more of a constant in the southwest because of grasses like Buffelgrass.

Driving at sundown on empty highways with the windows down racing through the desert in a rental car, there is an unmistakable specific freedom. It is openness. It is vastness. It is a freedom. Or, it may just be the colors in the sky or the feeling of warm air against your skin. Either way, Saguaro and their habitats are a part of that feeling.

Whether a respite from the recent age of tumult in the news or an appreciation of the past, present, and future of wild wilderness, Saguaros represent a continuum. The world may change, people get older, loved ones pass on, news cycles recycle, technology advances, possessions become useless, humanity prospers, humanity digresses yet certain things remain constant. The Saguaro will always be there.

-

Fragrant Swamps

(the story of the Venus Flytrap and the Green Swamp)

Each Spring, while others look ahead to upcoming plant sales, I think about the Green Swamp. Southeastern North Carolina’s Green Swamp is the home of a variety of carnivorous plants and the native range of the Venus Flytrap. The presence of Pines, specifically Longleaf Pines, shape and anchor these inland nearby coastal areas of southeastern North Carolina. The answer for how and why these areas came to be is found in the soil: acidic, peat based, nutrient poor, with a high water table. Further, the land, ecosystem, and history of its inhabitants is fire dependent. These elements combine to provide framework for a unique indigenous plant community of familiar faces, strangers, and oddities such as several species of distinct Pitcher Plants, some psychedelic sundews, aptly named Butterworts, unusually named Bladderworts, otherworldly orchids, and the Venus Flytrap.

The Green Swamp is incredibly diverse in flora, fauna, and history. In 1983, University of North Carolina (UNC) academics Joan Walker and Dr. Bob Peet, wrote a treatise on the “composition and species diversity of pine-wiregrass savannas of the Green Swamp, North Carolina.” To summarize, the fire-maintained plant habitat of the Green Swamp is amongst the most diverse in the United States. However, getting there isn’t easy.

While it appears closer on the map, the Green Swamp is not really close to anything. The coastal city of Wilmington is a far 41 minutes (36 miles) to the east and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina is almost closer. Exiting from I-95 east towards U.S. Route 74 drops you off on the long straightaway of flatwoods monotony. The roadside scenes repeat and cars drive in unison at the same speed. In situations like this, there is a tendency to be lulled into hypnosis. There is a magnetic pull clutching at your carwheels insisting you stay on the road and not exit. Fighting through this cosmic puppeteering, as you exit at Bolton, towards the town of Supply, time slows and ideas of distance are extended. It takes effort and perseverance to get there, driving through the rural pineland folk swamp world of North Carolina. There are no stores, no gift shops, and barely a sign announcing the Green Swamp Nature Preserve.

Perhaps because of grandiose National Park expectations, there is a specific anti-climax upon arriving at the nondescript dirt road parking area. There is a bulletin board structure with some general paperwork posted and a faded-out map of the Green Swamp. In my experience, there has never been more than a car or two in the parking area. On your immediate left, there is a sizable body of water shielded by a shrubby understory. Continuing on, the Green Swamp reveals itself slowly, transitioning in phases, often due to slight elevation and hydrology changes. The further you walk, the more difficult it gets to turn around.

Once you cross the barebones rustic boardwalk and through a ragtag section of overgrown shrubs (pocosin), the land opens up. On a good day, a steady breeze rolls through the canopy of pines. Visually, a color wheel of contrasts lie ahead with the bright color of carnivorous plants highlighted against a background of drably warm browns and greens. Even the living sphagnum moss covering the ground is vibrantly colorful. Despite being a swamp, the preserve is relatively easy to traverse – especially while staying close to the pine needle path. The skyward canopy of Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris) watches over the land with stillness and resolve.

Longleaf Pine infamously spend ten years as immature saplings, mimicking inconsequential grass clumps, before bolting upwards as trees. Upon closer inspection, the spiky three needle per bundle clumps are giveaways to their identity as pines and not grasses. In time, these trees become long, slender guardians of the forest and able to reach heights of 120’ with long 18’ needles atop their scaly orange brown prehistoric bark trunks. Patchwork clumps of Wiregrass (Aristida stricta) bind the plant composition together. Notably, Wiregrass mopheads cannot flower without fire.

Wherever there are noteworthy plants in the southeast, there is usually gunfire in the distance (often but not always from military training bases). Yet, at the Green Swamp, there is a peaceful, church-like zen atmosphere with intermittent sounds of Eastern Bluebirds and their cheerful low pitched warble, Red Cockaded Woodpeckers rhythmic peck, miscellaneous other sing song bird chirping, multitudes of insects buzzing, and the percussive sound of shoe sole stomps against spongy sphagnum moss. Note: I have never seen an American Alligator at the Green Swamp but I have seen them at the nearby Lake Waccamaw, often roadside, by water in small groups smiling in sun.

As mentioned, this Pine plant community is fire adapted. The pristine look of the Green Swamp land is due to periodic prescribed burnings, which clean up the landscape by removing overgrowth shrubs and trees which would in time shade out other herbaceous plants. Annual prescribed burns and land management, in theory, limit larger wildfires. But, incidents do occur. Evidence of the effectiveness of burning can be seen by driving to outside areas under different land management. These unburned areas are overgrown with a succession of trees, shrubs, and vines (often exotic) and an overall absence of light which limits the longterm growth of the understory plant material.

Longleaf Pines are long lived and sturdy. Many were historically logged and replaced with the faster-to-grow Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda). Notably, Loblolly and Slash Pine are not fire adapted. Longleafs have a history of being moneymakers too. Entire industries of turpentine with workers harvesting pitch from around the heartwood, migrant workers raking up pine needles to be farmed out to the local landscapers for mulch and, during the Revolutionary War, the British Army pillaged these trees for their upright, straight trunks soon to be ship masts. Interestingly, the hulls of the same ships were said to be sculpted out of the other famous coastal Carolina tree, the Live Oak (Quercus virginiana). Presently, the distribution of Longleaf Pines is only 3% of their previous range.

In 1974, the 15,907 acre Green Swamp was designated a National Natural Landmark though I am not entirely sure what that level of protection means. The boundaries of the preserve are loose and nearby residents live within or close enough to the preserve to serve as caretakers. Others ignore their proximity to the Green Swamp. Around these parts, watch out for official or unofficial hunting seasons. In the Carolinas, there is a complex series of dates, weapons and acceptable prey to be hunted almost year round. For example, Bobcat season is Oct. 18 – Feb. 28, Muzzleloader or Blackpowder only. Deer season is Oct. 2 – Nov. 19. Peak swamp bloom time is early May and into June so you should be ok. When in doubt, wear bright colors. People tend to stick to the paths in the Green Swamp. Where there is no path, muddy tire tracks from trucks make their own paths.

The Green Swamp preserve is the home of Venus Flytraps (Dionaea muscipula). However, disjunct populations in nearby Horry County, South Carolina also naturally occur. Other insectivorous plants, such as Pitcher Plants (Sarracenia), Sundews (Drosera), Bladderworts (Utricularia), and Butterworts (Pinguicula) all grow within the confines of the Green Swamp. Generally speaking, carnivorous plants grow in nutrient poor soil and have adapted, over time, to attract, allure, trap, and digest insects, gleaning nutrients from their hosts. They all have complex strategies of separately attracting duel sets of insects, for purposes of pollination and also digestion. Without exception, carnivorous plants have brightly enchanting colors, often neon. Pitcher Plants (Sarracenia) species (Red = rubra, Yellow = flava, Hooded = minor, and Purple = purpurea) are found in the Green Swamp. However, ranges of Sarracenia, especially Purples, are much wider (Maine and Michigan to Florida) than that of other species in the genus. Researchers have also found the insect paralyzing narcotic coniine on the lip of Sarracenia flava. This fascinating adaptation lulls insects into lethargy until they woozily fall into the pitcher.

Outside of cultivation, the Venus Flytrap only grows within the 50 miles of this area. Venus flytraps (or VFTs) are perennially growing plants known for their appearance and “active” carnivorous traps. Only one other plant on Earth, the aquatic and miniature Waterwheel, (Aldrovanda vesiculosa) is known to have active traps that snap shut. The manner in which the VFT works is complex: there are 3-5 trigger hairs on the inside of each trap, 2 of these hairs have to be touched within a few seconds, the plant then senses an insect and sends off turgid pressure of water moving through the plants and closing the trap. The reason for 2 trigger hairs and not 1 need to be contacted may be to mimic the walking habits of an insect and not to waste energy on debris falling into the trap. From there, the trap has to grow open in a manner similar to the new growth of the leaves of a plant. Each trap has a lifespan of several open and closings before they are replaced by new traps growing from the base. To reproduce, the Venus flytrap grows a tall white flower spike once a year which attracts a different set of pollinators than those of the traps. It would be futile to eat your pollinator. Aptly named, the latin Dionaea muscipula means Aphrodite mousetrap. Tippitywichit is another common name, used in England. The common name is understood to be a thinly veiled entendre for a toothed vagina. Arthur Dobbs, governor of North Carolina in 1763, compared the mechanics of the plant to “an iron spring fox trap.”

Walking in the Green Swamp is akin to going back in time. These protected and rural areas of the Carolinas feel unchanged from the Swamp Fox Revolutionary War, the exploits of plant collecting of frenchman Andre Michaux, the annual seed gatherings of the Bartrams from Philadelphia, the French-Indian Wars and the days of the Waccamaw Indians.

The story of the Venus Flytrap is a story of names and history. Below are some standouts:

Arthur Dobbs (1689-1765) was a Scottish born, British military officer who bought an absurd 400,000 acres of land in North Carolina in 1745. He was later elected Governor of North Carolina and attempted to establish a permanent capital site in northeastern NC called George City. In 1759, Dobbs, who lived in Brunswick Town across the bay from Wilmington south of Lehland, recorded the first written description of the Venus Flytrap. The now non-existent ruins of Brunswick Town is less than 30 miles from the Green Swamp. In a letter to Peter Collinson, an English merchant and avid gardener, dated to January 24, 1760,

“The great wonder of the vegetable kingdom is a very curious unknown species of Sensitive (my note: Sensitive Plant or Mimosa curls it’s leaves when touched). It is a dwarf plant. The leaves are like a narrow segment of a sphere, consisting of two parts, like the cap of a spring purse, the concave part outwards, each of which falls back with indented edges (like an iron spring fox-trap); upon anything touching the leaves, or falling between them, they instantly close like a spring trap, and confine any insect or anything that falls between them. It bears a white flower. To this surprising plant I have given the name of Fly-trap Sensitive.”

Peter Collinson (1694-1768), merchant businessman and plant collector famously corresponded with Philadelphian and “Father of American Botany” John Bartram (1699-1777). Bartram and Collinson never met but exchanged hundreds of letters and traded plants and seeds for more than three decades. Bartram was an ex-communicated Quaker from the town of Darby, outside of Philadelphia. He was later appointed “the King’s Botanist” to England and was the first person to bring the Venus Flytrap into cultivation.

William Barton (1739-1823), son of John Bartram, artist and author of Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscolgulges, or the Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians. Bartram writes enthusiastically of the “sportive vegetables” lining in the banks of streams and how “admirable are the properties of the extraordinary Dionaea muscipula!.”

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), a latin obsessed Swede who changed his own name to latin. ‘Father of Taxonomy,’ Linnaeus created the latin naming system based on plant flowers or plant sex. Linnaeus declared the carnivorous properties of the Venus Flytrap to be “against the order of nature as willed by God.”

William Young (1742-1785), dubbed the Pennsylvania Botanist to the Queen, imported living Venus Flytrap to another English merchant businessman moonlighting as a naturalist,

John Ellis (1710-1776), future Royal Agent for British West Florida, Ellis gave the Venus Flytrap the scientific name Dionaea muscipula. Ellis documented the VFT plant discovery to Linnaeus in 1770, Ellis included the first illustration of a Venus Flytrap in his essay Directions for bringing over seeds and plants, from the East Indies (1770).

Moses Ashley Curtis (1808-1872) was a Stockbridge, Massachusetts born Williams College botanist and Episcopalian priest who moved to Wilmington, North Carolina. Moses taught botany, advocated for the Venus Flytrap, published “Enumeration of Plants Growing Spontaneously Around Wilmington, North Carolina” in 1834. In 1986, a book titled A Yankee botanist in the Carolinas: the Reverend Moses Ashley Curtis, D.D. (1808-1872) was published.

Charles Darwin (1809-1882), Father of Evolution wrote the book Insectivorous Plants in 1892 where he obsessively studied the patterns and lives of carnivorous plants. He called the Venus Flytrap “one of the most wonderful plants in the world” with its “snap-buckling” traps.

The story of the Venus Flytrap evolves into the present day. Unfortunately, the plant and entire Longleaf Pine carnivorous plant ecosystem is threatened by habitat loss, changes in hydrology due to development and road building, and rising sea levels which dangerously add salt water to the habitat. A few years ago, there was a strange tale of a medical company looking for a cancer cure through poaching carnivorous plants. Though difficult to police, it is now a felony to take a Venus Flytrap out of nature. Thankfully, the plant is easily propagated by seed and tissue culture where labs, often in Florida, can genetically Xerox thousands in a day. Increased awareness has brought a conservation based mindset into the mainstream. North Carolina recently unveiled a Venus Flytrap license plate with partial proceeds going towards conservation and education. See the thorough yet complicated timeline here. In other news, there is a plan to expand a nearby road and its impact could have detrimental effects on the hydrology of the Green Swamp.

The Green Swamp experience shows there are botanical wonders hiding in plain sight and within driving range. The complicated yet fragilely connected network of plants, soils, trees, bacteria, fungi, insects, and mammals provide examples of interconnectedness and lessons for reliance in one another. The future chapters of the Green Swamp and the Venus Flytrap will depend on continued awareness and wonder in the natural world. This continued human curiosity will continue the story for future generations of plants, animals, and people.

nearby environs

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.